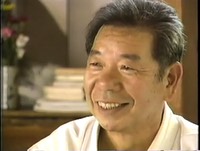

MORIHIRO SAITO (1928-2002) Biography by Morihiro Saito with Stanley A. Pranin.

After its defeat in the war, Japan was a poor, humbled nation governed by an occupation army. Morihei Ueshiba was residing with his wife, Hatsu, in the small village of Iwama where he had "officially" retired in 1942. The Ueshibas led a frugal life, growing rice and raising silkworms, assisted by a few live-in and local students who practices aikido under the founder.

Ueshiba was in his sixties and the possessor of a powerful physique resulting from decades of hard training. Freed for the first time in many years from heavy teaching responsibilities, the founder could at last pursue his personal training and ascetic activities with undistracted intensity. Although Ueshiba had taught tens of thousands of students prior to the war, the aftermath of the horrible conflict left him severed from all but a handful of his former disciples. The practice of martial arts had been prohibited by the General Headquarters of the Allied Forces, but this edict was unevenly enforced even in urban areas and was of little consequence in the countryside of Ibaragi Prefecture. During these early postwar years, Morihei Ueshiba called his country residence "Aiki En" (Aiki Farm) to deemphasise his martial arts activities, in deference to the GHQ ban.

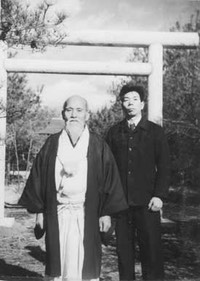

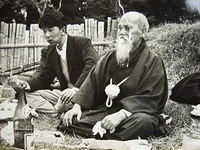

O-Sensei, Saito Sensei (early 1950's)

Morihiro Saito was a skinny lad of eighteen when he summoned up the courage to seek out the founder in the summer of 1946. He was born on March 31, 1928 in a small village a few miles from Ueshibas dojo. A typical Japanese youngster, young Morihiro admired the great swordsmen of feudal Japan such as Matabe Goto and Jubei Yagyu. Boys in Japan prior to and during World War II were embarrassed not to have some understanding of judo and kendo, and these arts were taught as a part of the required school curriculum. Young Saito had opted to learn kendo in school.

As a teenager Morihiro took up Shito-ryu karate in the Meguro district of Tokyo where he was then working. His karate training in Tokyo did not last long, as he soon moved back to Ibaragi Prefecture to work for the Japan National Railways. Saito then decided to take up judo because he felt that if he knew both karate and judo he would have nothing to fear in a fight. Judo was good in a hand-to-hand situation while karate was superior to kendo because on also developed kicking skills.

Saito recalls his early martial arts training and dissatisfaction with judo: The karate school was fairly quiet, but the judo dojo was like an amusement park with children running all around. That was part of the reason I became tired of judo. Also, in a fight, a person can kick or gouge whenever he wants to, but a judo man doesn't have a defence for that kind of attack. So I was dissatisfied with judo practice. Another thing I disliked was that during practice the senior students threw the junior students, using us for their own training. They would only allow us to do a few throws when they were in a good mood. I thought they were very selfish, arrogant, and impudent.

Morihiro's thinking about martial arts was, however, soon to undergo a major transformation. This was the result of a fortuitous encounter with an old man with a wispy, white beard who, according to local rumours, was practicing some mysterious martial art. Many years later Saito described his fateful first meeting with Morihei Ueshiba:

There was this old man doing strange techniques up in the mountains near Iwama. Some people said he did karate, while a judo teacher told me his art was called "Ueshiba-ryu judo." It was frightening up there and I was afraid to go. I had a very strange feeling about the place. It was eerie, but some of my friends and I agreed to go up and have a look. However, my friends got cold feet and failed to show up. So I went alone.

It

was during the hot season and I arrived in the morning. O-Sensei was

doing his morning training. Minoru Mochizuki directed me to where

O-Sensei was training with several students. Then I entered what is

today the six-tatami mat room of the dojo. While I was sitting there,

O-Sensei and Tadashi Abe came in. As O-Sensei sat down Abe immediately

placed a cushion down for him. He really moved fast to help O-Sensei.

Sensei stared at me and asked, "Why do you want to learn aikido?" When I

replied that I'd like to learn if he would teach me, he asked, "Do you

know what aikido is?" There was no way I could have known what aikido

was. Then Sensei added, "I'll teach you how to serve society and people

with this martial art."

I didn't have the least idea that a martial art could serve society and people. I just wanted to become strong. Now I understand, but at that time I had no idea of what he was talking about. When he said, "for the benefit of society and people," I wondered how a martial art could serve that purpose, but as I was eager to be accepted, I reluctantly answered, "Yes, I understand."

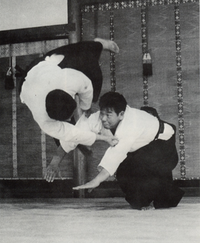

Then, as I stood on the mat in the dojo rolling up my shirt sleeves thinking of myself, "Well, since I've come all the way here I might as well learn a couple of techniques," O-Sensei said, "Come and strike me!" So I went to strike him and tumbled over. I don't know whether it was kotegaeshi or some other technique, but I was thrown. Next he said, "Come and kick me!" When I tried to kick him I was gently overturned. "Come and grab me!" I tried to grab him judo-style and again I was thrown without knowing how. My shirt sleeve and my pants ripped. Sensei said, "Come and train if you like." With that he left the mat. I felt a sigh of relief to think that I was accepted...

Although Ueshiba had accepted the young Saito as a student, the seniors at the dojo severely tested his resolve. Saito recalls the aches and pains of his early training days and how he felt it would have been preferable "to have been beaten up in a fight!" On one occasion during practice, he had to remove a bandage protecting an injury to avoid being ridiculed. If he showed the slightest trace of pain on his face, his seniors would torture that part of his body even more. Soon, however, the determined young Morihiro had proved his mettle and gained the respect of his seniors. He remembers with gratitude how he was kindly taught by people such as Koichi Tohei and Tadashi Abe.

The founder's teaching methods in Iwama were very different from his approach during the prewar years. In earlier years, it was his custom to merely show techniques a few times with little or no explanation and then to have students attempt to imitate his movements. This was the traditional method of martial arts instruction and students had to do their best to "steal" their teacher's techniques. But now, Ueshiba had the luxury of being able to devote his full energies to his personal pursuit with just a few close students.

As I look back on it, I think the brain of the founder was like a computer. During practice O-Sensei would teach us the techniques he had developed up to that point as if systematising and organising them for himself. When we would study one technique, we would systematically learn related techniques. If we started doing seated techniques, we would continue doing only that, one techniques after another. When he introduced a two hand grab technique, the following techniques would all begin with the same grab. O-Sensei taught us two, three or four levels of techniques. He would begin with the basic form, then one level after another, and finally the most advanced form. The founder stressed every little detail should be corrected. Otherwise it wasn't a technique.

The senior and juniors would practice together and the juniors would take breakfalls. When the seniors finished the right and left sides and the juniors' turn came, it was already time for the next technique. Though he didn't have many students at that time, O-Sensei used to throw everyone at least once. Sometimes while some of the senior students were practicing with O-Sensei, we waited our turn to be instructed by him personally.

Saito's job with Japan Railways was a stroke of good fortune as far as his aikido training was concerned. His work schedule of twenty-four hours on and twenty-four off left him free to spend a great deal of time at the Ueshiba dojo. As a result, he was allowed to participate in the early morning sessions normally reserved for live-in students.

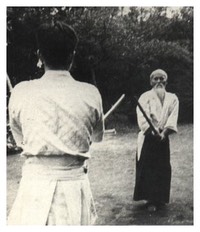

These morning practices consisted of about forty minutes of prayer while seated upright in front of the altar of the Aiki Shrine, followed by weapons training as the weather permitted. At this stage of his life, the founder was engrossed in the study of the aikiken and jo and their relationship to empty-handed techniques. He was experimenting with the basic weapons forms which Saito would later formalise into a comprehensive system to complement the empty-handed techniques of aikido.

O-Sensei just told us to come and strike him. Sword practice began from there. Since I had practiced kendo when I was a boy, I somehow managed to cope with the situation. Then he told me to prepare a stand for tanren-uchi, or sword-striking training. So I gathered some wood and used it to build a stand. However, O-Sensei got angry and broke it with his wooden sword. He said to me, "This kind of thin wood is useless!"

I had to think of something. I cut two big pieces of wood and drove nails into them and tied them together. When I made that Sensei praised me. However, even that stand lasted less than one week. So we struck at different places to save the wood. Then after a week I went out again to cut more wood in order to make a new stand. There were a lot of trees in the hills in those days. We used this setup to train in striking with the wooden sword...

As training advanced, we were taught what we now call ichi no tachi, the first paired sword practice. O-Sensei taught us this one technique for three or four years. The only other thing we did was to continue striking until we were completely exhausted and had become unsteady. When we had reached the point where we were no longer able to move he would signal that that was enough and let us go. That was all we did for morning practice every day. In the last years, I was taught by Sensei almost privately.

The widespread poverty of Japan in these years made it increasingly difficult for the few students at the Iwama Dojo to continue practicing. One by one, work and family obligations compelled them to abandon their training until only a few students came to practice. Seeing Morihiro's devotion and enthusiasm toward training, Ueshiba gradually began to rely on him more and more in his personal life. Finally, only young Saito was left to serve the founder on a regular basis. Even after his marriage, Morihiro's passion for training continued unabated. In fact, his young bride began to serve the Ueshibas too, and personally looked after O-Sensei's elderly wife, Hatsu.

In the end only a small number of senior students from this area and I were left. But finally, after they were married, they could no longer come to the dojo, since they had to work hard at their jobs. Whenever Sensei was here we would never know when he would call us to help him. Even if we had already asked a neighbour to help thresh rice, if Sensei happened to call us and we didn't come, the consequences were terrible!

Eventually, all of the students stopped coming to the dojo in order to maintain their own families. I could continue because I was free during the day though I went to work every other evening. I was lucky enough to have a job, otherwise, I wouldn't have been able to continue. I could live without receiving any money from O-Sensei because I was paid by the Japan National Railways. O-Sensei had money, but the students around here didn't. If they came to Sensei they would have had no income. they would not have been able to raise rice for their families to live on.

Serving the founder was extremely sever even though it was just for the study of a martial art. O-Sensei only opened his heart to those students who helped him from dusk to dawn in the fields, to those who got dirty and massaged his back, those who served him at the risk of their lives. As I was some use to him, O-Sensei willingly taught me everything.

The founder amply demonstrated his great affection for and trust of young Saito. When Morihiro took the initiative in helping O-Sensei favourably resolve a land dispute, he presented Saito with a parcel of land on the Ueshiba property. It was here that Saito built a home and where he, his wife and children lived and served the founder.

By the late 1950's, the years of intensive training under the direct tutelage of the founder had transformed Saito into a powerful man and one of the top instructors in the Aikikai system. He taught regularly in Iwama Dojo in Ueshiba's absence and was asked to substitute for Koichi Tohei at his dojo in Utsunomiya when Tohei traveled to Hawaii to teach Aikido. Around 1960 Saito also began to instruct on a weekly basis at the Aikikai Hombu Dojo in Tokyo and was the only teacher besides the founder himself permitted to teach aikido weapons there. His classes were among the most popular at the headquarters school and for many years Tokyo students gathered on Sunday mornings to practice free-hand and weapons techniques with Saito.

After

the founder's death on April 26, 1969, Saito became chief instructor of

the Iwama Dojo and also the guardian of the nearby Aiki Shrine. He had

served the founder devotedly for twenty-four years and O-Sensei's

passing only strengthened his resolve to make every effort to preserve

Ueshiba's aikido legacy intact.

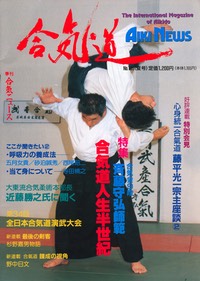

Over the years, Saito has established a wide network of instructors outside of Japan who teach "Iwama-style aikido", as his form of aikido has been informally christened. Iwama aikido has become synonymous with training with a balanced emphasis on emtpy-handed techniques and weapons practice, in contrast with many schools which train only in free-hand techniques.

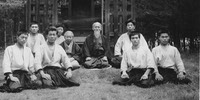

Presently the live-in system (uchi-deshi) for students continue in Iwama dojo and the live-in system gives participants of the opportunity to train intensively in aikido and learn the use of the aiki ken and jo. For the past twenty years, literally thousands of students have journeyed from abroad to study under Saito. Often the foreign practitioners outnumber their Japanese counterparts at the Iwama Dojo.

After unfortunate passing of Saito Sensei on 13th may 2002, his son Hitohiro Saito Sensei is continuing his six-day-a-week schedule conducting morning classes on the aiki ken and jo for live-in students and general practice in the evenings when he teaches empty-handed techniques. On Sunday mornings, weather permitting, Saito leads the general class outdoors, and provides instruction in aiki ken and jo.

Perhaps Morihiro Saito's success as a leading teacher of aikido lies in his unique approach to the art, his blend of tradition and innovation. On the one hand, he is totally committed to preserving intact the technical legacy of the founder. At the same time, Saito has displayed great creativity in organising and classifying the hundreds of empty-handed and weapons techniques and their interrelationships. Furthermore, he has devised numerous training methods and practices based on modern pedagogical principles to accelerate the learning process.

In the aikido world today, there is an increasing tendency for practitioners to regard the art as primarily a "health system" and the effectiveness of aikido technique is little emphasised in many quarters. In this context, the power and precision of Morihiro Saito's art stand out in great relief and, due to his efforts in the past and due to the efforts of Hitohiro Sensei and a few other dedicated teachers around the world, aikido can still be regarded as a true martial art.

1992

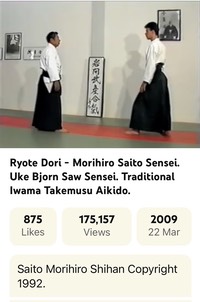

This is the background story of the video made with Morihiro Saito Sensei in Italy in 1992.

In January 1991 I was in Bodhgaya, India, on retreat meeting my guru to be, Andrew Cohen. After five weeks of being immersed in deep spiritual inquiry and meditation, an inner explosion took place that would change my life. This life transforming event is described in detail in my essay “Final Freedom” and can be found online but also in a published written softcover book. Leaving India in February I flew to Japan, and traveled back to Iwama that I had already visited on a couple of trips in 1987 and in 1989. I was staying in the Iwama Dojo (named by O Sensei “Aiki Shuren Dojo”) as an “uchideshi”, a live-in apprentice of Morihiro Saito Sensei, 9 Dan Aikikai. I was there for the remainder of the year practicing Aikido with a small community of dedicated Aikidoka both Western and Japanese. “My Time In Iwama”, also an online essay, describes my experience of living and training in Japan. During my stay in the dojo, many visitors came for a week or two from abroad to train with us. One of these short term visitors was Paolo Corallini, a dentist from Italy. He came with a couple of students, one who was his translator, a Japanese woman named Sonoko Tanaka (who I was later to marry). By the end of 1991 I was about to leave Japan homebound, but I first returned to India to spend another fortnight with my new spiritual teacher, after which in January 1992 I flew to Rome to spend time with Sonoko, then living in Macerata on the coast. Later that year Saito Sensei visited Paolo to hold a weeks summer camp. Before the camp started, Sonoko, who acted as Paolos translator but also was his Aikido student, I and Alessandro Tittarelli (student of Paolo at the time) spent the time together, having family dinners with Saito Sensei. It had been decided Sensei wanted to give Paolo a chance to record and film a whole set of Iwama basics over the next two days, partly as a thank you for dental work Paolo had provided Sensei with and for his dedication to Aikido. Alessandro and I were asked to be Ukes. At the time Alessandro suffered a bad back so he asked me to do most of the ukemi, especially all the highfalls. That’s why I feature in the majority of the clips. We filmed the full Saturday and Sunday before the seminar started on the Monday. It was made into a VHS tape lasting approxmately an hour and a half, which we later become privy of as we were all given a copy from Paolo. In the end of the film it states that the Copyright 1992 is Morihiro Saito Shihan, nothing else. So I wonder if that would give his surviving son Hitohiro any rights?

I moved to England in 2001 and opened the Aikido Alive London dojo, beginning a new chapter in my life, teaching traditional Iwama Takemusu Aikido on a daily basis. Sadly, Morihiro Saito Shihan, our teacher passed away in 2002 and we were left without the absolute authority on our way of Aikido and we also lost a direct source connection to O Sensei’s life in Iwama and we realised that we had to stand on our own, teaching to the best of our ability, carrying on the legacy Saito Sensei had left us—Riai, the combined system of bukiwaza and taijutsu (bokken, jo and bodywork), the way O Sensei wanted it. Now I knew I sat on a treasure with the video tape in my drawer. It needed to be shared to benefit and to preserve the "Iwama Style” that we so consciously knew was very special to any Aikidoka who cared for a deeper understanding and insight into the teaching methods of Morihei Ueshiba O Sensei.

So in 2009, seventeen years after we had filmed it, I converted the original VHS tape to DVD format and downloaded the film onto my computer. I set out to edit the movie into viewable segments based on each attack form, consisiting of all the basic techniques in our Aikido syllabus. It turned out to be 18 shorter clips to which I added a title and description. To start I only uploaded two clips to my YouTube channel: 12 Jo Dori and 9 Tanken Dori. No one objected and soon the views increased in volume into the tens of thousands, reaching a worldwide Aikido audience. Then a year later I added another two clips. Still no reaction and no complaints from Paolo or Alessandro. The following year I added the rest and soon the Iwama world had access to a complete syllabus in its basic form demonstrated by Morihito Saito Shihan for free on YouTube. Today the views are in their hundreds of thousands. Until today there has not been one objection, not one complaint, nor any copyright infringment claims—for sixteen years! Till now suddenly a few days ago Paolo decided to claim a copyright that on the original VHS film simply only state: Morihiro Saito Shihan, Copyright 1992. Within two days my YouTube channel had accrued three copyright strikes and 10 videos had been taken down as a result, jeopardising the whole site, warning it would be closed unless the claimant withdrew their claim. I was facing losing 202 Aikido videos, 10,200 subscribers, 16 years of work in an instant, unretrievable. I was at loss of what to do, so I appealed to the Aikido community online, questionong the whole unannounced procedure, with not one warning or call beforehand. No message, text or email had come from Paolo. I later learned he'd employed a law firm to do his bidding, pursuing the claims vigorously with legal precision and ruthlessness.

Today, 33 years after we had filmed and participated to make this testament to Aikido, suddenly Paolo think it’s time to claim it to himself. Why? I don’t really know but I can only venture to guess. Whatever the reason, he put me through the wringer, a nightmare of five days, and prolonged for several weeks since he was not able to retract his claim on my final clip left to be reinstated to YouTube, for me to download and then delete under the threat of legal action taken against me. Now I question his legality to this forced action, and seek to learn more of it. But I’m no match for a proffesional legal team ready to eat me up.

I’ve been given the chance to keep ONE clip out of eighteen, to appease me and to make me swear that I will not upload them again. It’s a hard pill to swallow knowing that Paolo himself have benefitted from the worldwide recognition this recording has gained online.

Kind regards, Bjorn